Introduction

This article summarizes an event hosted by the Global Grassroots Support Network (GGSN) and Leading Change Network’s (LCN) on Building Power with Land Defenders, held on the 19th of June, 2025.

57 people from more than 16 countries joined to hear directly from land defenders based in Guatemala, India, the Philippines and Zimbabwe. It was moderated by Jacob Okumu (GGSN coordinator and LCN member) and the event featured the following speakers:

- Sandra Portela, Xinca community member, Director of Alternativas de Desarrollo para las Juventudes y las Mujeres (ADEJUM) Izabal, Guatemala

- Christy Nag, Adivasi community member, Core member of Umul, an Adivasi led organisation in Dooars, West Bengal

- Christian Jake S. Tabara, Youth Campaign Officer for the Alyansa Tigil Mina (ATM), the Philippines

- Leonard Mabasa, Director for the Buhera Residents Network Trust, Zimbabwe

Speakers addressed how Indigenous land theft historically, and presently, is driving the need for land resistance efforts, and that there is no ‘just transition’ off fossil fuels without addressing the needs of the Global South.

More specifically, the presenters touched on; how communities can be empowered through storytelling, that building up a diverse community network builds resilience, that building broad alliances with one common goal is effective, and empowering most affected community members with knowledge and skills builds ownership.

“There was an old proficiency that would say that when the planets are about to collapse, we need to become warriors of the rainbow. And this is important to recognize and value our colours, our differences. And this comes from inside, to the outside because we know that oppression and inequality is already there.” -Sandra Portela, Director of Alternativas de Desarrollo para las Juventudes y las Mujeres (ADEJUM) Izabal

You can access the whole edited transcript here.

You can view and hear the full english recording of the session here:

And vea y escuche la grabación completa en español de la sesión aquí:

La transcripción en español se puede consultar junto con la grabación de YouTube.

Indigenous land theft historically, and presently, is driving the need for land resistance efforts

IN INDIA: Community education and storytelling empowers community members to take part in resistance efforts

The British built the tea plantations (pictured below) in Adivasi communities through violent coercion and deception. Adivasis were held captive for labour, and were denied land rights and mobility. The colonial state supplied just enough to keep them alive to exploit their labour.

“Due to the colonial state they had easy access to land, but to establish the tea plantation they needed a huge workforce… they uprooted and displaced Adivasis from their village.. they lost their forest, they lost their rivers, they lost their way of life and what did they get here? A life with no dignity.” -Christy Nag

In 1951, the plantation labor act was supposed to guarantee housing, healthcare, food and education to permanent workers. No tea company has implemented the act in full in Assam and in West Bengal. Around 50% of the workforce in the tea gardens are temporary workers, who do not have statutory rights.

The minimum wage act was enacted but does not cover tea plantation workers. Tea workers earn about $1.38 USD)/hour less than the minimum wage. The image below shows some of the temporary workers of tea the plantations.

“There is again silence from the state and the unions have failed… in 2023 what the West Bengal government decided is to give away land to the tea companies. Earlier the land was given to the tea companies on lease, but in 2023 West Bengal government said okay we will make the tea companies owners of the land.

Here the key question is what will happen to the homes? What will happen to the workers living and working in the tea garden? The other thing is this amendment [says the land can be] used for tourism. It can be used for an industrial park. There’s no limitation to the usage of land.” -Christy Nag

The tea gardens land has 2 zones; one is the cultivation zone (managed by companies). The other is the village zone where people have built their homes and have kitchen gardens. Communities are declaring the land where they have been living and surviving, is theirs historically.

“From Umul, we organize a community library and we work with children and youth and women, primarily talking about what we have been discussing [in this event]. We have extended discussion around these things with the communities, primarily knowing our own story, our histories, what are the laws, and the other work that we do is around collectivization.” -Christy Nag

Question for Christy: How and why unions have failed in India?

“If we look into the union structure at the ground level, there are workers who are doing the footwork of the union, and at the top level you will not find workers and you will not find Adivasis. It is led by the Bengalies. So, even if they start negotiations with the state and the tea companies, slowly over time they give up because it is not their fight at the end of the day.

In West Bengal, the Trinamool congress party is the ruling party and at the national level BJP is the ruling party who have formed the government in West Bengal. West Bengal is run by trinamul congress and India is run by BJP, it has formed the government in India… The unions are affiliated either with TNC or with BJP, and in Assam BJP has formed the government…. when the union is affiliated with the ruling political party, then the same political party is designing laws with the colonial mindset.” -Christy Nag

Follow and amplify Umul: Instagram

IN GUATEMALA: Developing a diverse community network builds community resilience; a necessity against violence

ADEJUM collective is formed by women and Indigenous youth, trans women and non-binary people in the rural areas. They live in Machacas Puerto Barrios in Guatemala. The Machacas river provides water for communities of the region.

The water system is collapsing due to several projects that are related to fertilizer production, and oil and gas. The projects are being positioned over rivers and lakes, and the main root of the Machacas river.

ADEJUM collective is resisting 5 projects. They have been persecuted with firearms of high caliber for their resistance to a project that is close to the river bend of the Machacas river. The river is an ancestral area for recreation, fishing and bathing.

“This has forced us to move from our territory, [and caused the] social death of our community. Collectively it has made us invisible also to keep our colleagues safe, to keep a low profile, and also to understand when we can raise the bar, raise our profile and when we need to keep quiet in order to protect our safety.” -Sandra Portela

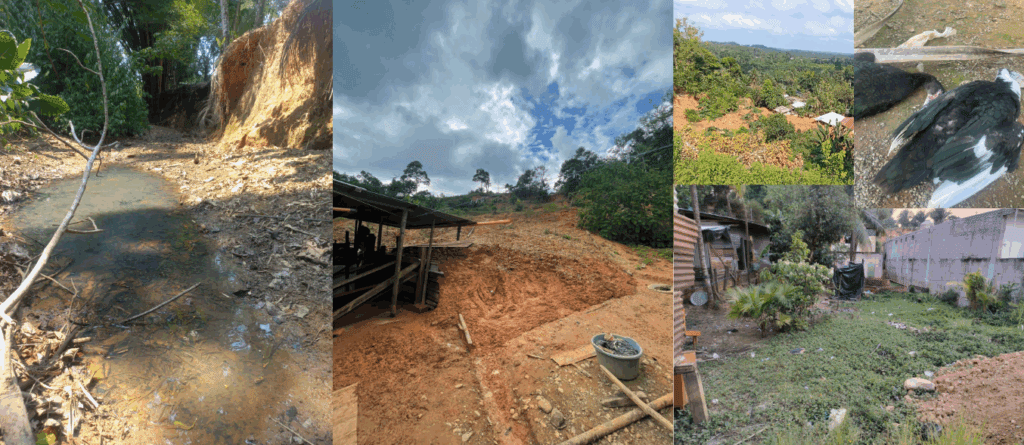

The projects are changing the ecosystems of swamps in the region. This is causing destruction to homes, notably impacting marginalized community members such as children, disabled people and elderly people. Sandra explained that species of duck and chickens that drink the water are dying, and they fear for their children that play and fish in the water. This is shown in the images above, shared by Sandra.

The collective has brought the issues to authorities through different voices and channels, from people who understand and live in the community.

“We are Indigenous people, Xinca, Maya and there’s a wide diversity of people living here in this area and we are trying to move forward step by step and we always say that fear is inherited and we are trying not to pass down fear to our children. We’re trying to raise our voices because we know that we don’t want our children to be scared from their guns.” -Sandra Portela

Community members are trying to participate in the recovery of the water systems through clean up days and forest replants. Some community members are shown in images shared above by Sandra, anonymized to protect their identities. The collective is fighting for the recognition of the river as a sacred being, not just a resource, to be honoured, supported and enjoyed by generations to come.

“We’re trying to develop the community network through different activities, related sports, cleanups, campaigns to prevent violence. We’re also trying to develop our traditions and communicate with our sacred spirits for them to give us the kind of strength to save our water system.” -Sandra Portela

Their call to action includes the protection of different species present in the Machacas, many of which have been lost. They are seeing animals coming back to the area. The collective needs communications support from organizations to prepare their storytelling and narratives to buy the swamps land for it’s protection.

This image, shared by Sandra, is of a local Otter threatened by activity from the projects they are resisting.

Follow and amplify ADEJUM Izabal:

There is no ‘just transition’ off fossil fuels without the Global South – examples in the Philippines and Zimbabwe

IN THE PHILIPPINES: Broad alliances with one common goal are building widely supported campaigns

Alyansa Tigil Mina (ATM) is a coalition of mining affected communities, local organizations. ATM is not advocating to ban all mining. Rather, they are advocating for an end to large scale mining which exploits mineral resources, undermining the value of land to Filipinos.

In the Philippines, there are 6 financial agreements with over 103 hectares of land being mined. There are 49 registered community mines.

“This mining is also exacerbated with the just transition that the global north is pushing for the energy transition for solar energy, wind energy or e vehicles. But there are communities in the Philippines that are suffering because of these transitions. So the just transition is kind of absent in the process and there are sacrifice zones like the Philippines, Indonesia and some parts of the global south.” –Christian Jake S. Tabara

The image shared above is of mining resistance in Cibuan Island, Harlon. Police are shown assisting a mining truck with the transfer the mineral ores.

Where there’s mining, there’s drought, air pollution, water pollution from their extraction, and other kinds of pollution. There’s also a disruption of livelihood for farming, fishing and the use of ancestral domains.

“[There is a] biologically dead river in uh Marindok, one province in the Philippines. So they declared the river as biologically dead, meaning after the tragedy where the mine tailings were, [they] spilled in the river and up until today the river is totally dead.” –Christian Jake S. Tabara

Based on the global witness report, the Philippines is the number one place in Asia where land and environmental defenders are threatened, and worse, being killed. The Philippines is third in the whole world after Brazil and Colombia.

In the Philippines, companies are joining the race for a position like Senate or Congress to ensure that there’s no laws being passed that delay their businesses. There is weak legal enforcement of environmental laws and accountability mechanisms. The government or the ministry of environment is selling the Philippines to foreign investors, effectively greenwashing mining operations in the country.

“We do community assemblies, Indigenous councils in Barangai level or village level to raise awareness amongst mining affected communities and create support from those who are not directly affected. Say, for example, in Metro Manila or universities near mining affected communities. And we also create solidarity networks among farmers, fisher folks, youth and translating it into more marginalized sectors like women, members of the LGBTQ, disabled people. So we’re also in the process of creating policies for these things and then we also have public campaigns, legal and policy engagement and cultural resistance.” –Christian Jake S. Tabara

Calls to action for the public include advocating to learn more about the effects of mining, and to support grassroots efforts through donations, volunteering and amplifying their stories. Create and share content to highlight local struggles and victories, and advocate for community-based alternatives like solidarity economies, ecotourism and agroecology.

For the government, they are calling on officials to enforce stricter environmental regulations, ensure environmental laws are observed, and to prioritize renewable energy and a just transition in communities.

The video above sums up the work of ATM. It includes a song composed by young people in the Philippines called “Ipamana Huwag Ipamina.” Ipamana means to inherit or to pass on. Huwag means don’t and is for mining. it translates to inherit it, don’t mine it.

Question for Jake: What lessons can you share about how you can build power together with organizations across diverse perspectives?

“We’re engaging the Catholic church as well because they have a push for influence. I mean, they are good partners when it comes to conservation of the environment. Then we have different religious groups as well, and academic institutions. So what we need to do is to create a popular version of our research so people from different sectors are engaging with it.” -Christian Jake S. Tabara

Follow and amplify Alyansa Tigil Mina:

IN ZIMBABWE: Empowering most affected communities with knowledge and leadership skills builds momentum

The Zimbabwe government is projected to have a 12 billion economy by 2030 due to an abundance of natural resources (lithium, gold, phosphate, coal, diamond, nickel, iron etc). In Buhera (average population of 170,000), land represents life, stability, dignity and livelihood.

23 households were pushed from their ancestral land to relocated in Murambinda, an urban area. In 2024, it was found that the mining company Sabar Mine paid, who paid for each family to build a five room house, prejudiced their land size by 70 square meters to 120 square meters. 1,910 square meters were stolen by the local authority.

Engagement meetings were done in 2024 to compensate for the white collar crime. Compensation has not been done. The case is still being pursued.

“2 million litres of water is required to process one ton of lithium. Pollution of underground water and contamination in mine communities is a cause for concern. We did water testing for one bowl in 2024 and the results showed high nitrates, meaning the water is not suitable for drinking. The burden is for women, children, and [disabled people who] walk nearly 2 km distance to look for clean water as shown [in the picture above]. They fetch water a distance from their residence and they were using a vehicle that was offered by the counsellor in ward 14. ” -Leonard Mabasa

The image above, shared by Leonard, is of a burial shrine after the exhumation process. There was no emotional support for the deceased’s families.

Excessive abrasion of water causes water scarcity. Dust pollution impacts flora, fauna and over 2,000 school children along the 30 km gravel road that links the main road and the mine.

“Issues to do with harassment, intimidation and sexual exploitation are issues in the line of work. Below 18 years in terms of the law are not eligible for marriage or any form of sexual engagement. But because of mining, the girl child is at risk of sexual manipulation.” -Leonard Mabasa

Buhera Residents Network is empowering local women with knowledge and training, and documenting human rights violations. They keep online (including social media) and print media informed on the injustice happening at and around the mining site.

“To build a strong united front through the Buhera resident trust, we have trained 25 women to be women human rights defenders so that they can speak of injustice in their settlement. This is beefed up by 22 community leaders whom we train to document violations, be it environmental, social, economic or political.” -Leonard Mabasa

The next tool they are trying to employ is exploring the Ramsar convention guidelines. They are assessing whether the wetland can be accorded a national or international wetland status, which may aid in conservation efforts.

Follow and amplify Buhera Residents Network:

-

-

-

-

- For news updates, join the Enviropress Zimbabwe WhatsApp group

-

-

-